Who is today still putting into question that when we speak about instincts, body, movement, thought, emotions, spirituality or faith, we are only referring to and putting into words limited aspects of a more global experience of life ?

The distinction between mind and body was probably perceived as an obvious truth by the artist who, more than 18.000 years ago, painted the Shaft Scene on a remote wall of a chamber at the end of a 5 meter long shaft of difficult access deep in a cave. The scene shows a naked man lying down, with his penis erected, next to him you can see a spear-thrower decorated with a bird, a spear and a disemboweled bison.

Stanislas Dehaene, on the first page of his book Consciousness and the Brain (2014)[2. Le Code de la Conscience – Stanislas Dehaene – Odile Jacob 2014 (English translation : Viking Press 2014)], gives us an explanation for the Shaft Scene borrowed from Michel Jouvet, a French sleep specialist.

The symbolism of the bird

Before Jouvet, the presence of the bird was only seen as an allegory : a symbolic bird, extended to the bird-like face of the man and his four fingered hands – to the extent that we can talk of a bird-man. This symbolic bird represents the soul of the dead which flies into the next world, as in many religions and mythologies, or even the mind of a shaman in trance travelling into another world.

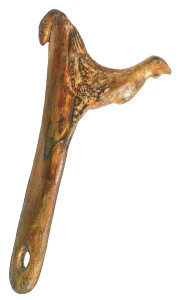

Spear-thrower (Magdalenian period or Age of the Reindeer – 15.000 to 10.000 B.C. – Upper Paleolithic) Masdazil Cave – France

The spear-thrower with its ending sculpted in the shape of a bird becomes itself a symbolic bird which helps the soul or the mind to leave the body, in the same way the spear leaves the spear-thrower to travel longer and faster than with bear hands. The bird tells humans that they are more than just flesh and blood and that they can travel beyond their physical anchorage to the Earth.

The Shaft Scene, Lascaux Cave, Upper Paleolithic (around 18.000 B.C.)

This rock drawing from Lascaux Cave associates four elements : a man lying on his back, in erection, a stick ending with a sculpted bird, a wounded bison with his viscera coming out of his belly and a broken spear. Many interpretations have been proposed. Henri Breuil thinks it represents the commemoration of an hunting accident. Horst Kirchner sees a shamanic scene showing a wizard in a trance. With much reservation I propose the following hypothesis : the artist of Lascaux wanted to show at the same time a man dreaming, the concept of dream and the content of a dream. We know today that erection occurs during paradoxical sleep which corresponds to the oniric activity in humans. This erection occurs independently of the content of the dream, either it is erotic or it is not. 20.000 years ago, our ancestors must have noticed this physical manifestation during the dream, which was only rediscovered in 1965 by Charles Fisher. During the dream, the soul (represented here by the bird, like the human manifestation Ba in Ancient Egypt) leaves the body. It is possible that the bison, wounded by the spear, represents the subject of the man’s dream] sees a man sleeping and dreaming (the erection of the penis is present during the dream phase of sleep.) The bird is still the symbol of the ‘soul’ which leaves the body and let him see a wonderful hunt : a dream hunt somehow.

Clearly this imaginary scene cannot possibly be the result of this inert lying body.

The direct and immediate perception

Lacking our knowledge, the prehistoric man was facing here a counter-intuitive situation : instead of a global experience, he was perceiving two distinct phenomena : on one side the dreamer and on the on the other the sleeper.

We know, thanks to this representation, that this way of thinking, which separates the mind and the body, was born at least 18.000 years ago. This conception has travelled through the centuries with a great deal of success and has been reflected upon by the greatest thinkers of the past and of today.

And because we feel that there are at least two levels of beings in us (later in history more subtle levels have been added), we tend to make a distinction between the body and the mind, which leads us to conclude that one can act and take control of the other and dominate it : in other words that my will can dominate my body.[4. This leaves us with the question : who is I ?]

The body and mind dualism

This idea of control of the mind over the body has maybe never been as present as today, while at the same time the research in neurosciences tends to show that unity is not only within ourselves but that we are one with the world and the universe, in a complete interdependence. To the extent that never before have the consequences of the attempts to control Nature for the benefit of the human beings have been experienced as a threat to our species to such an alarming point.

Our society, and all the industrialized societies in the world, which are increasing day by day in these times of globalization, are requiring the same thing from the individual: more efficiency, quicker results, better functioning, without any regard to the means involved and the consequences to their health and well-being. More and more is expected, as though people could submit their bodies and mind without any limits. We are pushed to convince ourselves that we can achieve everything we want and dream of without taking account of the element of time and our real physiological needs.

On top of it, many of us have reached the stage where we ourselves expect and seek perfection. Many of us are organizing our lives like a business and try to achieve perfection in everything as though we were super humans : perfect parents, perfect lovers, perfect bodies, fulfilling hobbies and responsible citizens.

A real tyranny for the body which needs to be efficient in all fields : beauty, strength, speed, efficiency. It has to be obedient ! Like a good machine !

All this has a high price, which bears fashionable names : stress, exhaustion, burn-out, chronic fatigue, depression, and even suicide.

Detachment

It is no coincidence that fashionable words like relaxation, zen, mindfulness, meditation, slow food, yoga, etc attract a lot of people dreaming of the promises of experiencing inner states of quietness and freedom, or for those who already practice them finding time to enjoy them more fully.

All these approaches have a common denominator that the word detachment seems to summarize best. Detachment implies an inner distance, standing back, stopping and thinking, connecting with ones center, reorienting oneself. Or simply to taking the time to breath mindfully.

Here we clearly have one of the paradoxes of the modern human being. In order to overcome this ancestral dualism still operating in ourselves, which was born from the direct and immediate perception that body and mind are two separate entities, we need to consciously create an inner space, stand back inwardly and take the time to accept ourselves as a global being.

The unity of self

F.M. Alexander, at the beginning of the 20th century, shared a different view along with some other pioneers as we can read in the extract below that he wrote in 1932 in his third book The Use of the Self :

The Alexander Technique offers the possibility to make the experience of the unity in the use of oneself in movement. It offers the possibility to discover that we act and react as unified beings and that any uncontrolled habit, fixation or excessive tension is a tangible proof of that by limiting our freedom by interfering with our actions.In becoming aware of habits which limit us, we can learn to integrate them and choose to enter into movement and action without their influence, and discover other ways of doing and being.

Conclusion

The over stressed human being dreams of being ‘zen’, of finding inner peace, because his mistreated body can’t take it any longer. Too much is expected from him. He feels treated like an insensitive machine. [5. Some might argue that machines exhibit some form of intelligence and sensitivity. But that’s another story.]

Fortunately, he knows today that he can keep on dreaming, which is an integrated part of our life, but he does not need anymore to leave his body to do so. Happiness belongs to this world and to this moment.

The shaft scene – Lascaux cave in Dordogne (France) [1. The Shaft Scene: Lascaux Cave was discovered by chance in 1940 and was definitively closed to the public in 1963 because of the deterioration of the paintings due to humidity and heat caused by the overwhelming amount of visitors. A partial replica of the cave was opened in 1982 not far from the original cave. A new more complete replica is due to open in 2016 one km away from the original cave. ]

The Shaft

In the floor of the Apse is a hole (now occupied by a ladder) giving access to “the Shaft of the Dead Man” a small part of an underlying cavern known as the Great Fissure. It is the deepest, most confined part of the entire cave. At the bottom of the ladder and on the adjoining wall is one of the most remarkable prehistoric pictographs yet discovered. The main scene depicts a fight between a bison and a man: the bison has been stabbed by a spear and appears to be dead. The man has a bird-like head and is stretched out as if he too is dead. Lying next to the man is a bird on a pole. Not surprisingly, given the fact that humans are almost never depicted in Stone Age paintings, and that complex narrative scenes like this one are equally rare, the pictograph has attracted fierce debate as to its precise meaning. Strangely, there are very few other pictures in the Shaft. Only eight have been found: four animals (bird, bison, horse, and rhino), and three geometric signs.