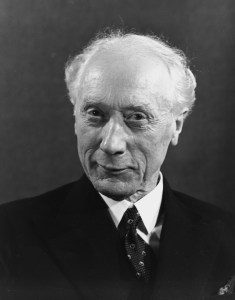

Fredrick Matthias Alexander was born in Tasmania in the year 1869. As a child he was often ill , too ill to go to school and so he was educated at home. He developed a passion for the plays of Shakespeare and left home in his early teens to take voice and elocution lessons in Melbourne with view to becoming an actor. He formed his own theater company which toured New Zealand and he knew some success, however he often experienced hoarseness and the loss of the power of his voice during performances.

Fredrick Matthias Alexander was born in Tasmania in the year 1869. As a child he was often ill , too ill to go to school and so he was educated at home. He developed a passion for the plays of Shakespeare and left home in his early teens to take voice and elocution lessons in Melbourne with view to becoming an actor. He formed his own theater company which toured New Zealand and he knew some success, however he often experienced hoarseness and the loss of the power of his voice during performances.

The many doctors he consulted recommended rest cure. Sometimes he would not speak aloud for two weeks before an important recital, but even under these very strict conditions he found it hard to get to the end of a performance without his hoarseness reoccurring. His capacity for logical thinking obliged him to conclude that there was something in what he himself was doing which was causing the problem and his doctor agreed. When he asked his doctor what this was his doctor admitted that he could not tell him. With this Alexander set about finding the cause for himself, armed only with three mirrors and his unique powers of observation.

He noticed that when he got ready to recite he tensed his neck muscles which pulled his head back and down. At about the same time he took in a noisy gasp of air which compressed his vocal cords and tensed his body as a whole which appeared shorter. Alexander found ways of altering this habit of getting ready to recite and the result was after a long period of practice his voice problem disappeared.

The improvement in his performance was so noticeable that others asked him how he had achieved this, and as he started to observe others as a result of their questions he noticed that far from being a problem which affected only himself , the problems of gasping in air, tensing the neck, throwing back the head and depressing the vocal cords was very widespread and affected almost everyone in varying degrees. As he applied himself increasingly to helping his fellow actors it was not long before doctors started to send him their patients and in the end these people outnumbered his pupils from the arts seeking to improve their performance.

At this stage F.M. as he was known recruited his brother A.R. to join him in teaching the technique he had developed and he transferred his practice to Sydney where they were both soon inundated with work. It was J.W. Steward McKay, a famous surgeon at Lewisham Hospital who tried to persuade Alexander that the technique which he had developed was of such great value to man that he should travel to London in order to secure his work the recognition that it deserved. He set sail for London in April 1904 and until the outbreak of the first world war he gave lessons in his technique to many of the famous people of the time in all walks of life as everyone is concerned by the way in which we move. His first book, Man’s Supreme Inheritance was published in 1910.

During the war he went to America and almost every year from 1914 to 1924 he crossed the Atlantic in October and returned to England in the Spring. In 1920 he married Edith Page and they adopted a daughter Peggy. In 1923 Alexander’s second book Constructive Conscious Control of the Individual, was published. Professor John Dewey and Dr Peter MacDonald both helped him to describe in words the experience of what he wanted to convey.

In 1930 Alexander set up a training course for Student teachers, and in 1932 published The Use of the Self which was the best selling of his four books in the U.K. although it did not do as well of some of his other books in the U.S. In the years before the second world war he achieved the greatest recognition for his work but once again the war interrupted the flow of pupils so in 1940 at the age of seventy-one he set sail for America with his teaching assistants. He published The Universal Constant in Living before returning to London in 1943 and after the war worked hard to set up his training course for teachers again. In 1947 he had a stroke which left him paralyzed on the left side and doctors gave little hope that a man of seventy-nine could overcome such crippling consequences, but within a year he was again giving lessons to others in mobility, and continued to do so until his death in 1955.